Most evenings, my six year-old son and I take a walk through our crowded apartment complex to a little man-made lake where we throw rocks, look for fish, count ants, all that.

Sometimes, the dog-walkers take the trip too.

My son is scared of dogs.

He worries they’ll either attack or lick him. Which means he’s scared of mean and friendly dogs.

“Don’t worry, my dog is nice,” a pleasant elderly man always says.

It doesn’t matter, pleasant man. Your dog is a dog.

So how do I handle this?

As a loving parent, how would you handle this?

Well, I hold my son close and say, “Don’t worry, I’ve got you. I won’t let anything happen to you.”

Now does that help?

Maybe a little.

And the reason I know is because he leans in closer to me, and holds onto my arm, and we eventually make it to that lake.

But he’s still petrified for those few minutes. And he doesn’t let go of my hand until the dog has gone.

I hope you can see where I’m going with this.

In Matthew 6, Jesus tells us not to worry at least four times and nine verses are devoted to shaking us from our worries.

Over the years, Christians have used this passage as the basis to call worry a sin, and as such, really mentally torment worriers.

The crux of their argument: “If Jesus says ‘don’t worry about tomorrow’, that’s a command. ‘Don’t’ means don’t. Therefore, it’s a sin to worry.”

I’ve heard it a million times.

And do you know what that does to chronic worriers? It makes us worry even more.

So are we sinning?

There are two reasons why calling worry a sin is a disastrous misinterpretation of Matthew 6.

First, think of the example above.

When our child is worried about something that we’re in control of and we tell them, “Don’t worry about that dog. He’s on a leash and I’ve got you,” are we issuing a moral imperative?

Is it the same as when we tell our child, “Don’t punch your brother?”

Clearly, no.

What we’re really saying is, “You don’t have to worry about the dog. I’ve got you. I’m your protector. I’m your dad. I’m going to hold you, and there’s no way I’m going to let that dog attack you.”

It’s not a warning about sin. It’s an assurance of protection.

Let’s take another example.

Imagine you’re out to dinner with a friend and the bill comes, and you stop your friend from pulling out his credit card and say, “Don’t worry. I’ve got this.”

You’re not issuing a moral imperative.

You’re promising him that you’re paying the bill, he’s under no obligation to reciprocate, and guess what, you actually want to do this.

He doesn’t have to worry that you don’t have the money, or that he’s free-loading, or that this is putting you out.

If you were actually issuing a moral imperative, there’d be fist-fights breaking out at Olive Gardens all across the country.

When we say “don’t worry” to our children, our friends, to anyone, we’re not chastising them for doing something morally wrong.

We’re saying, “My son, my friend, you don’t have to worry. I’ve got this.”

And that’s exactly what Jesus appears to be doing.

Read through those nine verses, think about them, and then ask yourself, “What idea is Jesus trying to get across? What’s the gist of his message?”

The answer is clear: He’s talking to us as though we’re frightened little children, and offering comfort, “Children, you don’t have to worry because the Father loves and cares about you.”

This isn’t a passage of moral warning, it’s a passage about the warmth and love and character of the Father.

Look at the central line right in the middle of the passage: “If God cares so wonderfully for wildflowers that are here today and thrown into the fire tomorrow, he will certainly care for you.”

God’s the Dad, we’re the children, and he’s got us because he loves us.

And so Jesus’ chat about worry isn’t about our moral character. It’s about the Father being a Father.

Matthew 6 isn’t a seven deadly sin passage, and tragically, it’s often presented that way when Christians talk about it.

One more thing.

When my son freaks out and holds onto me tightly, there are two things I focus on.

First, continuing to try to relieve his fear by assuring him of my protection.

And second, the fact that he’s still trusting me by holding, tightly.

And that second point is key.

Worry drives my son closer — not farther — from me, and it should drive us closer to our Father.

If my son truly didn’t trust me, he’d let go of my hand.

But when he gets closer to me, even in his worry, he is showing great faith.

David spent nearly all the Psalms worrying about things, but he also spent all of the Psalms talking to God.

“I believed in you, so I said, ‘I am deeply troubled, Lord’.” – Psalm 116:10.

In this passage, faith didn’t soothe his troubled heart. It took that troubled heart to God.

In fact, every prayer of petition is based on some worry, at some level.

Now, there’s something else that throws cold water on this idea that worry is a sin.

Anxiety is a protective, physiological response, and its definition is also completely arbitrary.

If you didn’t worry at least a little bit, you’d be dead.

You wouldn’t get your heart checked, you wouldn’t go to to the store to buy food because you wouldn’t worry, “What happens if I don’t eat tonight?”

And that’s where the “worry is a sin” crowd gets itself into another jam.

If a little worry is necessary for living, then who’s to say when too much worry is too much worry?

It becomes totally arbitrary.

Your worry is my “prudence.” My “prudence”, to you, is my sinful worry.

It’s all a matter of interpretation, and “worry” will be defined differently by different personalities.

So it doesn’t make biblical or theoretical sense to call worry a sin, and so we should stop worrying about that part.

Now of course there’s the final part to that passage in Matthew 6 and it needs some clarifying because it’s the second responsibility we do have.

“Seek the Kingdom of God above all else, and live righteously, and he will give you everything you need. So don’t worry about tomorrow.”

The Greek word for worry is better translated “anxiety” or “to care for” or “distracted by.”

And therein lies our responsibility.

We can’t let our worries distract us from our number one pursuit: living as disciples of Jesus.

Is your worrying keeping you from loving others?

From being tender-hearted, from humility, from living in peace with the people you don’t like, from turning the other cheek?

If it is, then your worries are, indeed, distracting you from the kingdom of God, and that’s a problem.

In that case, worry still isn’t a sin, but it’s leading to one.

So, for example, if I’m worried about my job and lie to keep it, that’s a problem, because I’m letting my worry get in the way of my spiritual responsibility to tell the truth.

If I’m worried that I can’t pay my rent and and rob a bank, then I’ve got a problem.

In those cases, worry is keeping us from seeking the kingdom of God.

But I suspect that, for you and me, for those with generalized anxiety disorder, that’s not where our worries take us.

If you keep praying, despite (and often) through your worries, if you keep loving others, despite (and often) through your worries. If you keep pursuing peace, despite (and often) through your worries. If you do all that, you are seeking The Kingdom of God “above all else’ and that’s the point.

So don’t let the “worry is a sin” crowd turn this passage into something dark and shaming.

Instead, think of a loving parent who holds you, no matter your worry, and will keep holding you, no matter how much you tremble.

(P.S. If you want to explore the biology of fear, of worry, the science behind it, here’s a great breakdown. Obsessive worry is also a symptom of a medical condition, and I’ve talked about that a million times. This post is just a response to those who raise theological objections, and ignore the clinical aspects of it).

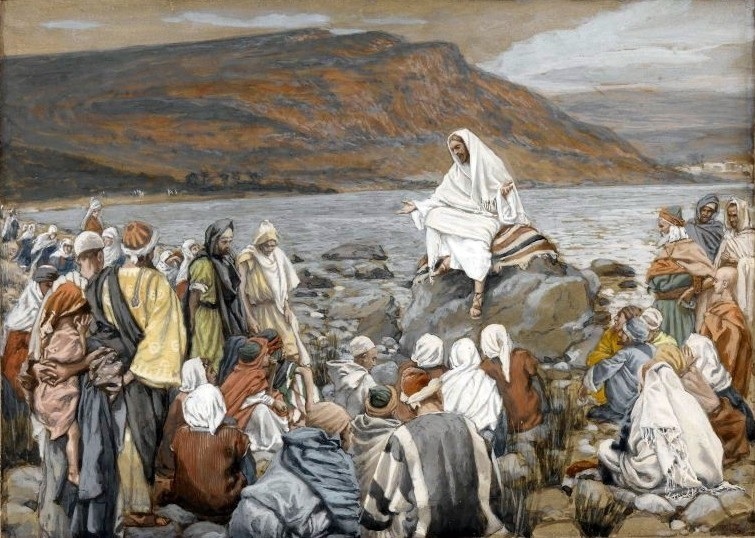

[Painting: James Tissot, Jesus Teaches The People by the Sea, 1896].

Christian Heinze is a former writer for The Hill.