Psychology Today has a tremendous review of some new results, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, from a Stanford team of researchers on a modified form of TMS (transcranial magnetic stimulation).

Read Stanford’s news release, too.

But here’s a shorter version of the story.

iTBS is a modified form of TMS, and stands for “intermittent theta-burst stimulation.”

In 2019, the FDA approved iTBS for major depressive disorder.

The good news is that it helps some people.

The bad news is that only about 32% of people with treatment-resistant depression experience a reduction in symptoms.

That leaves a lot of room for improvement.

Enter Stanford University and its team of researchers who decided to modify iTBS by accelerating both the dosing and timing of that dosing (They called it Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy or SAINT).

In traditional iTBS therapy, you get 600 pulses/day for six weeks.

In Stanford’s trial, they delivered 1,800 pulses/day, and they did it TEN TIMES per day and for only FIVE days, instead of six weeks.

Besides the dosing difference, they also did more precise targeting, which I won’t get into here, but in the study itself, the authors note why the accelerated delivery might have made such a difference.

Multiple, spaced sessions have also been shown to produce accumulating nonlinear improvements in clinical symptoms (41, 43). The duration of intersession intervals is likely to be important, as stimulation sessions with intersession intervals of 50–90 minutes have been shown to have a cumulative effect on synaptic strengthening, whereas sessions with intersession intervals of 40 minutes or less do not show this cumulative effect (15–17, 44). Similarly, some studies have shown that two theta-burst stimulation sessions delivered to the motor cortex 15 minutes apart do not increase cortical excitability compared with a single session (42, 45). Finally, left DLPFC activity has been shown to be correlated with sgACC activation 10 minutes after rTMS; this correlation was reduced 27 minutes after rTMS, and the correlation between these regions reached its nadir 45 minutes after rTMS (10), the hypothetically optimal time for stimulation. Taken together, these data could explain the limited response rate (39%) of a previously reported accelerated iTBS stimulation protocol for depression (24, 25)

The results last year were impressive and immediate, and confirmed in a new study they conducted this year.

They found that, after a simple 5 day treatment (which was found to be safe and well-tolerated — the only side effects were fatigue, some discomfort at stimulation site and in facial muscles during stimulation), depression symptoms lifted for 78.6% of participants by a whopping 52.5%, using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale.

The “sham treatment group” or placebo group only saw their symptoms decline by 11%, proving the statistical significance of the SAINT treatment.

Dr. Nolan Wilson, senior author of the study, says, “It works well, it works quickly and it’s noninvasive…..It could be a gamechanger.”

Alan Schatzberg, a professor of psychiatry at Stanford adds, “It’s quite a dramatic effect, and it’s quite sustained.”

Stanford Medicine on the implications.

Because the study participants typically felt better within days of starting SAINT, the researchers are hoping it can be used to quickly treat patients who are at a crisis point. Patients who start taking medication for depression typically don’t experience any reduction of symptoms for a month.

“We want to get this into emergency departments and psychiatric wards where we can treat people who are in a psychiatric emergency,” Williams said. “The period right after hospitalization is when there’s the highest risk of suicide.”

This is tremendous news.

Most psychiatric hospitals, due to insurance demands, only keep patients for a few days to a week for “stabilization” and that usually means providing a safe environment where the patient can begin a new drug regimen and undergo intensive counseling.

But it often takes medications a month or more to work, and upon discharge, patients lose access to both the dedicated team of therapists and the safe environment. (In 2019, Psychology Today wrote of the “dire state of inpatient mental health.”).

A five day course of SAINT’S iTBS “could” (more studies are needed) save a lot of lives — not only because it seems to work often for the most severely depressed, but also because there are a lot of “medication-resistant” patients who don’t want to try a lot of new meds.

Note: Medscape has a write-up on the study, as well.

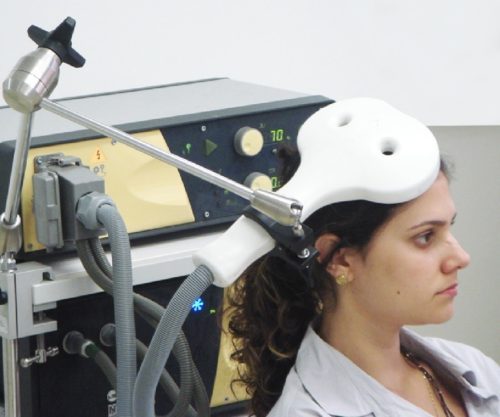

[Photo: Wikipedia, a woman sits for a session of TMS]