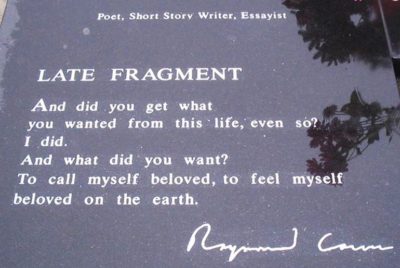

If you walk by the great poet and short story writer’s tombstone in Port Angeles, Washington (or, more easily, see it on Google images), you’ll find inscribed his poem, “Late Fragment.”

“Late Fragment“, Raymond Carver

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

Some are so fortunate, others not.

And when you or I fall into our funks, it’s easy to question everything good, and certainly, to feel “beloved” is the greatest good there is.

A few things on that.

First, I’d recommend this read by Janna Lim on the relationship between pessimism and depression.

They’re not the same thing, but certainly associated with one another, and very often, our pessimism — the thing that keeps us from allowing us to feel beloved — stems from childhood.

A “pessimistic attributional style” develops where we expect that “the happy moments won’t last long and negative events will return.”

My favorite “pessimistic attributional style” song is “Miserabilism” by the Pet Shop Boys.

It seems to me

There’s something serious beginning

A new approach found

To the meaning of life

Deny that happiness

Is open as an option

And disappointment

Disappears overnight

Say that love

Is an impossible dream

Face the facts

That’s what it’s always been

Relax

What you see is what you see

And what you get

Is a new philosophy

Fun song, huh?

Sometimes I quote the lyrics to a friend and they say, “Well, that’s miserable,” as if they’ve never thought of it, and it’s somewhat astonishing to me because I feel I’ve known those words since before they were written.

Psychology Today has a very interesting read on pessimism, and it’s a complex topic that tends to run with depression, but there’s something called “depressive realism,” and I think that’s what “Miserabalism” is getting at.

In my circle of depressed friends, we often use our “depressed realism” as a coping mechanism for the fact we do live in a world where happiness and pain seem to come and go with brutal indifference.

Acknowledging that is okay for me, fixating on it is not.

Because “depressed realism” can quickly become “deep depression,” and that’s when we don’t even recognize the moments of happiness and if we, by odd chance do, we don’t trust it.

We almost run from it, because we see the end of it before the end of it comes.

And this all comes back to the point of feeling “beloved” and the remarkable armor it provides.

To feel “beloved on earth,” as Carver wrote, is beyond anything you will find on earth, and to feel truly beloved must come from an unconditional love, and time itself is often the only proof of it you’ll find.

When Jesus says to forgive one another, 70×7, he’s urging us to a) offer unconditional love, but only because b) we’re his disciples, and that’s what he gives us.

Jesus would never call us to love in a way he doesn’t.

And so when I find my wife forgiving me, over and over, for the same sins that exhaust us both, but never seem to exhaust her love, that’s when I can somehow believe that kind of love is possible from God.

And that’s the kind of disciples Jesus wants us to be. The ones that prove his love is possible.

And that’s why I always go back to quoting authors like Brennan Manning and Henri Nouwen, who are merely quoting Christ and the Scriptures when they relentlessly note that we are eternally, unconditionally, forever “beloved” by Christ.

John Eagan writes: “The basis of my personal worth is not my possessions, my talents, not esteem of others, reputations, not kudos of appreciation from parents and kids……I stand anchored now in God before whom I stand naked, this God who tells me ‘You are my son, my beloved one’.”

God would not have sent his son to die for you, if he did not love you as deeply as his own son.

That’s the Good News and it seems so good that we often find it the “Too Good To Be True News.”

It is so hard for depressed people to accept they are beloved by anyone or anything — let alone the God of the universe.

I sometimes pray to God, “You know I don’t really believe you love me, but please love me nonetheless.”

And he does.

Imagine your child, for a second.

Let’s say he’s depressed and doubts you and everyone else’s love. Does that affect how you feel about him?

No, in fact, if anything it makes your heart break and long for your child’s happiness more than anything, because you love them so much.

You can see their pessimism and depression getting in the way of that, and it doesn’t make you say, “Fine, if you don’t believe it, then guess what, I DON’T love you!”

No! That’s not how it works in a parent-child relationship.

A good parent loves their child no matter the child’s misconceptions, brought on by their depression or pessimism.

If we don’t see ourselves as beloved by God, we are still as beloved as Christ himself.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to believe that here on earth.

But I’m guessing that once this earth is over, Christ himself will stand with me, overlooking paradise and say simply with a smile, “See?”

And I’ll finally see Revelation 21:4, not as a collection of words or a painting that’s impossible to reach, but I’ll be in the painting myself.

“There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.”

And then I’ll see just how beloved I was all along.

You will, too.

God will prove the pessimist in us wrong, just as he did at every turn while on earth.