Really, you could headline anything regarding men and anxiety as “quiet epidemic,” because a) men rarely talk about their anxiety and b) we’re often super anxious.

The Wall Street Journal noted what you already know — in general, men are too scared to talk about their anxiety, and so it comes out — not in healthy ways — like seeking medication, therapy, or chatting. But instead, through irritation, anger, substance abuse, and chronic pains.

And I say that pointedly: Men are too scared to talk about their anxiety. Why? Because they don’t want to seem scared. Which is a rather scared thing to do.

I’m not trying to shame. I hate telling people I’m anxious, as well. But I think (know) that God would rather we acknowledge and seek help for our anxiety than blow up at our families, abuse drugs, and live with seething bitterness (bitterness usually seethes, doesn’t it? That’s the operative word).

Now, in the world of new parents, most pay attention to the struggles of new moms, and post-partum depression is an extraordinarily serious and prevalent phenomenon.

But the media and our communities are much quieter on new dads who suffer sudden anxiety and depression.

Writing in Very Well, Sarah Simon has an excellent look at all the reasons why new dads are more likely to suffer from anxiety than, well, pre-dads, and they’re what you might expect — a host of new practical responsibilities, existential crises (what am I now?), a reorganization of the spousal relationship, financial pinches (strollers and bassinets and sound machines and, oh, by the way, if you get the wrong one of any of these — the cheap one — your kid might die).

Women tend to form supportive communities to help soften the blow of all this (Baby Center, Moms groups etc), but is there anything for men? Nothing. And it’s not because we don’t need it. It’s because we’re too scared to say we need it. And there it is again. Guys, we’re too scared.

Now here are some numbers.

Researchers estimate that around 18% of women struggle with anxiety during the perinatal period. Meanwhile, 11% of men struggle, post-partum. Now, take into account the fact that men tend to be more scared at reporting anxiety, and the numbers are probably pretty comparable.

There are long-term effects to this.

Simon notes that many men experience what’s called acute stress disorder during this time, and that is often the precursor to PTSD. PTSD can last a lifetime. Your child can be grown and gone, and you can still be suffering from PTSD.

That’s why it’s so critical to get help as soon as you start feeling overwhelmed.

Now I’m not going to sit here and bash men by using that loaded phrase, “toxic masculinity.”

“Toxic masculinity,” while a real and terrible thing, is tossed around about everything these days to the point that it’s going to start damaging our boys’ mental health.

As Simon notes, there is such a thing as “healthy masculinity” and “positive masculinity” and we should celebrate it.

But what does that look like?

In order to achieve healthy masculinity, Singley says we need to start early. “If we, as a society, could make the changes necessary to socialize boys to be healthier, then we don’t have to fix broken men and fathers,” he says.

These socialization skills, Singley adds, involve teaching boys how to keep from shutting down emotionally, and how to navigate intimacy in platonic and romantic relationships. “Being able to say what they’re feeling—the good, the bad and the ugly, and not to teach them that it’s weak.”

Studies have shown just how important it is for kids to start identifying and naming their emotions from an early age.

Whine about snowflakes all you want, but the science is clear — kids who talk about and name their emotions are much less likely to develop depression later on. And, God have mercy, none of us wants to see our child endure the pain, the horror of depression. Call me a snowflake all you want. Let it blizzard snowflakes, and I won’t care if it keeps my children from going through what many of us do.

I was talking to a friend, recently, who has a fraught relationship with his dad, and he told me that if there was one thing he wished he’d seen more growing up — it would be his dad, crying, showing weakness. Something he, as a child in his weakness, could relate to.

How did his dad answer? “Dads don’t show weakness. It’s a terrible example.” And that was that.

But Jesus wept, Jesus showed emotion, and it’s precisely those moments that we all feel closest to him.

In fact, a beautiful truth of Christ is that he was so emotional. He wasn’t too scared to cry in front of others. To talk about his coming suffering. To even compare himself to a mother hen. When was the last time you heard a tough dude do that? And yet Jesus did.

I want to finish with this — it’s a quote from Frederick Douglass that Simon pulls up, and it’s one for all of us parents of boys to remember:

“It’s easier to build strong boys than to repair broken men.”

To poach the late James Boice, “Amen. And amen.”

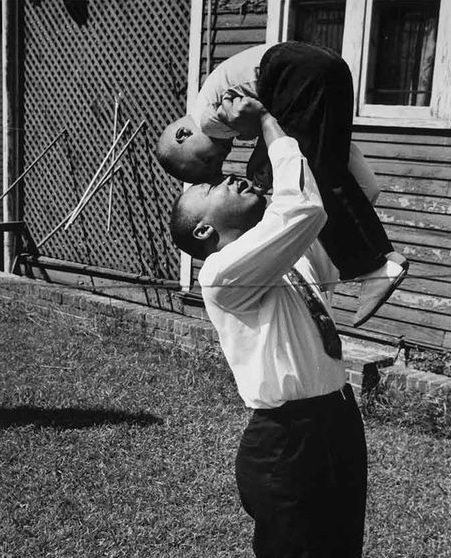

[Photo: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Martin Luther King III, James Karales. Cropped. Smithsonian]