The two simple background facts for this interesting, new study.

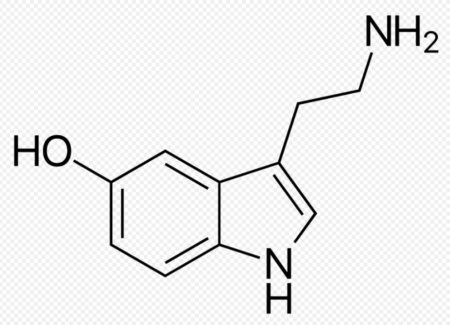

First, there’s a neurotransmitter in the brain called serotonin. It’s often called the “happy chemical” because it helps stabilize our mood and feelings of well-being and it impacts the whole body.

You’ve heard it before — not enough serotonin (or serotonin imbalance) and you’re set up for depression and anxiety. Thus, we get SSRI antidepressants that seek to increase or rebalance serotonin levels in the brain.

Second, serotonin has a transporter protein, 5-HTT, and it “pumps serotonin away from the cerebral neuron synapases.”

So theoretically, the higher your levels of 5-HTT, the lower your levels of serotonin, because more serotonin is getting pumped away, right?

Now here’s where it gets strange.

Studies have shown that people with depression actually have lower levels of 5-HTT (the transporter) which doesn’t make immediate sense, at all, because that would suggest depressed people have more serotonin in the brain. Or at least, not as much serotonin getting pumped away by 5-HTT.

Well, a brand new study published in Translational Psychiatry suggests, yes, we need to think about rethinking how the serotonin system works in depression.

Researchers treated 17 patients with depression and found that 13 had significant improvement. Great.

Now here’s the interesting thing — after treatment, their levels of 5-HTT averaged about 10% higher than the healthy control group.

In other words, depression treatment raised the levels of the transporter (5-HTT) that pumps serotonin away from the brain!

What does it mean, though?

Researcher Dr. Johan Lundberg explained in the news release:

“One possible interpretation is that the serotonin system doesn’t cause depression but is part of the brain’s defence mechanism for protecting itself against depression.

One might hypothesize, for example, that the level of 5-HTT drops when an individual is subjected to stress, such as during a depressive state, and that the level rises or normalises when this stress goes away.

It’s important to point out, however, that even if these ideas are raised by our study, its design doesn’t allow us to draw any conclusions about why levels of 5-HTT change.”

https://eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2021-05/ki-sti050621.php

This is just another important piece of the depression puzzle, and shows how inscrutable a medical condition it really is. Any brain condition is.

And that’s why it’s so hard to find an antidepressant that brings immediate relief, because everyone is different.

I recently wrote about a wonderful new study, though, that suggests we’re getting closer to finding the right Rx on the very first try.

Researchers at the Indiana University School of Medicine developed a blood test, “composed of RNA biomarkers, that can distinguish how severe a patient’s depression is, their risk of severe depression in the future and their risk of future bipolar disorder, or manic-depressive illness.”

Oh and, crucially, the test then gives doctors the tools to pick the Rx that would work best for you. Without theoretically having to try every singe one on the shelf.

I do think that we’re getting closer to the point where we can go to Quest or LabCorp, get our blood drawn, and then get a great Rx recommendation within a week.

That, of course, would be wonderful and would save so, so many lives.