Dr. Susanne Babbel has a good piece at Psychology Today on some of the important distinctions between trauma and PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder), and how treating trauma effectively can help prevent it from turning into its more insidious progeny – PTSD.

Her key point: “Trauma is less about the event itself and more about how the body and mind respond to it.“

We experience trauma after going through an event that puts us in fight-or-flight survival mode, which Peter Levine defined as “the experience of being overwhelmed by life-threatening events which exceed one’s capacity to process the experience at the time.”

Of course, whether it’s an objectively life-threatening event or not is beside the point.

One person might say, “Hey the bomb went off 100 yards from me! I wasn’t even close to getting hurt!” Another person might think, “But it was only 100 yards away.”

So don’t get hung up on whether your experience meets the criteria of “life-threatening,” because sure, watching your house burn down on TV while you’re in a different city might not threaten your life, but it changes it dramatically and traumatically, doesn’t it?

I think the key point in Levine’s definition is that a traumatic experience occurs when it “exceed[s] one’s capacity to process the experience at the time.”

That’s when we get into flight-or-fight survival mode, and if that persists for over a month, then PTSD starts to become the issue, and PTSD is a far more difficult beast to address than the triggering trauma.

So what to do if you face trauma?

Well, first get in touch with a doctor (psychiatrist or therapist – links below).

That’s always the “first” for any medical condition – whether you break a bone or experience a trauma (of course, we can pray on the way to the doctor, but we can’t overly spiritualize bodily disease).

Also, Babbel notes just how important community support is in healing. For example, her own research shows that survivors of 9/11 experienced far less trauma than survivors of Hurricane Katrina, thanks to a disparity in community support, socioeconomics, displacement and media portrayal.

There are many things we can’t address (to society’s discredit, the poor will will never have the resources of the rich for health).

But finding community and connecting with existing community is utterly vital to help keep trauma from becoming PTSD.

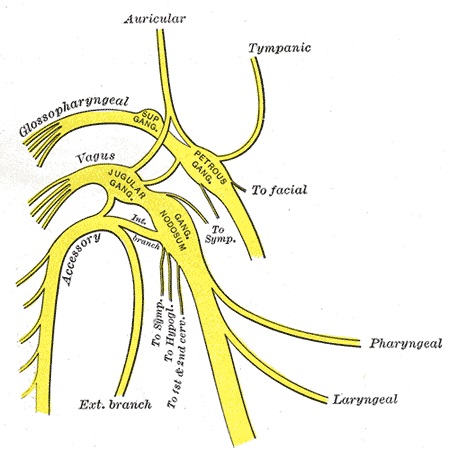

Babbel also recommends bodily things like vagus nerve exercises, breathing exercises, and practicing the emotional freedom technique (if someone thinks EFT tapping is mumbo-jumbo, then they’re arguing against compelling research, showing it can make a huge difference in relieving symptoms of PTSD – not just in veterans but nurses and other cohorts).

I want to finish on this concept of community.

Recently, I wrote about how difficult it is to connect with community (or even find it, or have the courage to find it) when you have PTSD.

Both the process and the connection can trigger another wave of trauma if you encounter the wrong community, and it’s absolutely vital to sort through this with a doctor.

I’ve found the Christian church a real hit-or-miss on trauma.

Sometimes community has brought me great relief; other times, it’s only brought additional trauma that’s worsened by the fact that it’s at the hands of the community that’s supposed to be the hands of Christ.

You might have experienced the same.

There are thousands of testimonials of Christians who found anything but support in the church when going through trauma and it’s a black mark of shame on the church, because Jesus came to those living with traumatic wounds, PTSD, every kind of malady, and he feels so heartbroken by the heartbroken that he spent his life, healing our wounds, and used up his death, to heal our transgressions.

Jesus treated the sick in body and sick in sin with distinctly different approaches, and the church should show a similar approach.

Too often, the church has used an inherent distrust of psychology to abuse victims of those suffering from trauma and PTSD, and if you’ve been a victim of those diseases and an indifferent church’s response to it, my heart and prayers go out to you (if you want a poignant account of this, read my interview with author Sarah Robinson, who went to a church that treated her depression as though it were a failure of faith, and thus, sent her into a further spiral).

That is not the heart of Jesus. The heart of Jesus was a bleeding one, and he is the only one on earth or heaven who can look at your pain, and say I know, I care so deeply for you and mean it to the point of the cross.

So again, look first in the direction of a therapist or psychiatrist, and then see if you can find a community that won’t abuse your pain. Hopefully, your church looks something like the community that can help in you healing! But if it’s not, I understand and, in the absence of the church’s support, have often found help from the kindhearted, regardless of spiritual belief.

If you suspect you have PTSD, are anxious, depressed, or struggle with any aspect of mental health…

For readers from the United States….

Find a psychiatrist here.

Find a therapist here.

For readers, internationally, seek help from a local resource.

For salvation, Christ and Christ alone.