Over the past ten years, there seems to be a growing global awareness that mental health care is, demonstrably, a medical condition and therefore, like any medical condition, a universal problem.

Every person dies from something because the human body breaks down, no one is immune from sickness, and mental health is physical health.

The distinction is, increasingly, seen (based on very good research) as arbitrary and a relic of incomplete understanding – much as the roots of many medical conditions were thought to lie other than the body.

Of course, that’s something a lot of people (and various cultures and even countries) aren’t prepared to accept, but each passing year, the reality becomes harder to deny.

The wave of research, personal experiences, and increasing openness on the topic is too overwhelming to deny, although there will always be those who deny certain ealities, and unfortunately, there will always be pockets in any community (including the church) that are among those ranks.

As the globe increasingly reckons with the scope of the problem (including within the church in the United States, and elsewhere), we often do so with an assumption that everyone has at some kind of access to diagnosis and treatment.

That’s simply not true.

Even in the richest of countries, access to mental health care can be extraordinarily difficult.

There simply aren’t enough doctors, therapists, and facilities equipped to deal with the problem in the hardest-to-reach communities and countries.

And without access to a qualified psychiatrist, millions have to live without potentially life-changing medication or other forms of professional treatment for their chronic mental health diseases.

Enter… Artificial Intelligence.*

The Economist has a wonderful article highlighting both the challenges and game-changing possibility of artificial intelligence’s ability to help people struggling with both geographic and socioeconomic difficulties.

I’ll give you the nutshell version, or you can read the whole thing here.

The challenges: In its infancy, AI has struggled with numerous aspects that are critical for diagnosing things like anxiety and depression.

For example, studies have shown that its accuracy can be significantly swayed by things like race, gender, local linguistics, jargon and many of the intricacies that, at first, seem only possible to recognize if you’re another human being aware of all those distinctions.

Chatbots might be popular, but they’ve got lots of serious problems, at this stage, and when you’re dealing with a medical issue, relying on a “serious problems” approach isn’t a great idea.

Consequently, it’s easy to see how AI could not only hinder, but actually hurt efforts to get an accurate diagnosis. A wrong diagnosis can be as damaging as none.

But AI-powered solutions don’t have to be just about chatbots.

There are much more sophisticated and empirically promising approaches forthcoming.

The more promising approaches: The Economist notes that researchers at South-Central Minzu University in China developed an AI model that uses extensive, personal learning of an individual’s patterns of speech, voice, and other things that are “too subtle for the human ear to detect.”

This remarkable level of “pre-training” in preparation of diagnosis delivered good results in a study published in Nature Scientific Reports.

It was 96% accurate in detecting depression and 95% accurate in detecting its severity based on a clinical rating scale.

In other words, not only did it almost always diagnose your depression correctly, it was also able to judge its severity, which is an even more remarkable achievement.

Other researchers across the globe are developing their own models that aim to address the limitations of AI by integrating things such as spectrograms that offer an extremely detailed visual map over time of an individual’s voice etc.,

It’s an even more complex model, and its sophistication could go beyond diagnosing depression and into a broader set of mental health diseases.

(Of course, we know that AI is already being considered and used in treatment of other medical conditions, so this isn’t a dramatic leap in theory – just application).

Further, private investment in AI for mental health is exploding, and startups across the globe (including Egypt, France, Poland, Kenya, the United States, the UK etc) are popping up as founders hope to bring this technology to fruition.

As we know, venture funding only follows promise – it usually won’t flow in the direction of failure (I wish this were the case, personally, for selfish reasons), so this is a good sign.

It’s even more encouraging to see just how global this movement is.

I’d guess, for example,that regulatory rules and stigmas would be more manageable in Egypt for Egyptian-based startups etc. The more global this movement, the better.

Now, let’s say all this pays off and researchers can get to a point of high accuracy in diagnosis. That’s great!

But there are a couple important things to remember.

First, there’s a difference between a diagnosis and treatment.

The AI I’m writing about can’t treat mental health conditions. It’s primarily about diagnosing it (a tricky word itself).

So the treatment barrier exists, and theoretically, regulatory issues would vary dramatically from country to country.

So even if you have personal access to a highly accurate diagnosis, that doesn’t mean a psychiatrist would be easy to reach.

Maybe there are very few doctors in your community or country, and maybe laws would prohibit medical treatment based on AI diagnosis, and in countries with insurance, who knows, and in countries where medical care is free, there’s the burden of getting the government to buy into this.

Those are all going to be issues going forward that studies like these can’t address, except to offer a starting point proving AI can be extremely accurate at diagnosing problems.

There’s another thing to mention.

If you have access to a psychiatrist and can afford it — AI tools seem to be something that the doctor and you could possibly use together, but it’s really hard to recreate, via AI, the sense that you’re being cared for in an appointment with another human being.

That component is crucial, and for those fortunate to have access to that kind of regular treatment, I can’t imagine how AI could ever replace such a critical human experience as that in-person visit.

Personally, I can’t make the in-person visits anymore, and yeah, there’s a huge difference.

But again, that’s a luxury most of the world, sadly, doesn’t have. Even in the richest countries.

Finally, for Christians…

I know that some Christians can be leery of this brave new world of AI. We see all kinds of things like the rare AI robot pastor headline, and some Christians are especially prone to seeing a world, devoid of humanity, true connection, and even truth itself.

The truth is – many pastors already use some form of artificial intelligence, and most of us do, without thinking any time we go online or do much of any interaction with the world.

But anytime you put AI with something as sensitive as mental health, you’re going to get pushback. And I get the distrust of something that’s designed by humans to replace human roles.

That has both economic and moral implications.

But we already have so many things that fit that exact sentence: “something designed by humans to replace human roles.” And we rightly don’t bat an eyelash about it, because the world is better off for it.

There was a time, obviously, before computers, before cars, before any kind of development. Every new technology disrupts something, and there’s a time for mourning for some that’s difficult but ultimately represents progress for most.

And is distinctly amoral. Jesus got around, occasionally, on a boat. Gutenberg’s printing press contributed heavily to the Reformation and gave millions access to the Bible.

There were many who resented that and invoked religion to do so.

Like any new thing, AI can be used for harm or good. Man made fire, and along with it came arson. The tradeoff has benefited mankind.

If AI can offer people a diagnosis of their medical conditions, if it can help expand access to those diagnoses and hopefully, treatments, then I see it as a mercy from God.

Others might disagree and remain uncomfortable with it. That’s their right and always will be. (My hunch is that they don’t struggle with depression or anxiety etc., and live in the realm of “this is something you can just solve with a Bible, and you can get one of those practically anywhere in the world.”).

I never want to shorten the hand of God, but science and medicine and life-changing stories and empirical studies have all confirmed that this is a medical condition, and while access to a Bible can certainly help us as we deal with the pain — we are born with bodies susceptible to disease, and thank the Lord for medical care.

If you’re depressed, or struggle with any aspect of mental health…

For readers from the United States….

Find a psychiatrist here.

Find a therapist here.

For readers, internationally, seek help from a local resource.

For salvation, Christ and Christ alone.

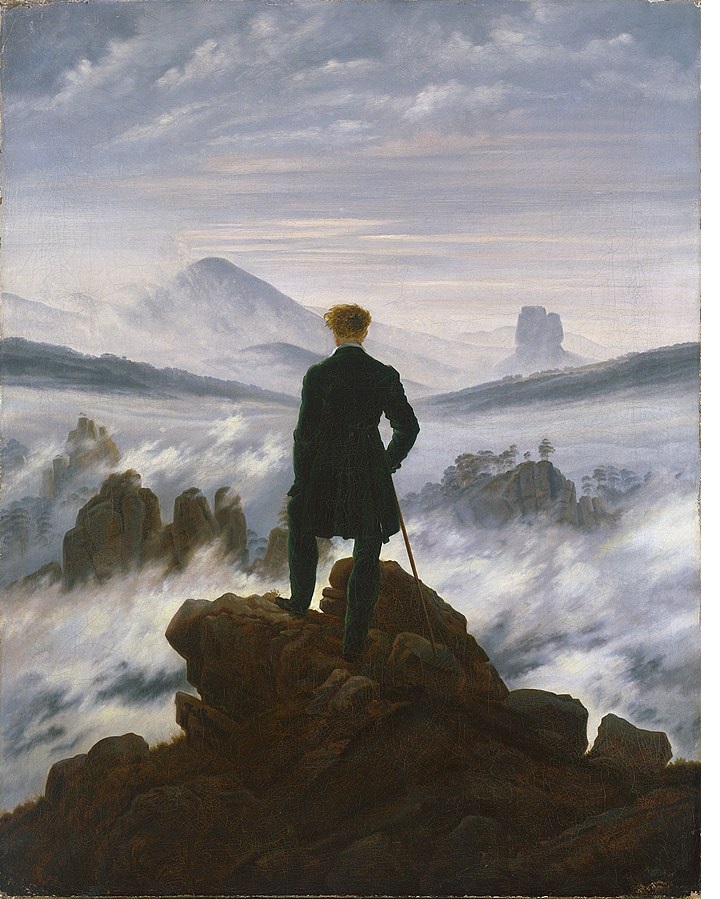

[Photo: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, Friedrich. I eschewed the obviously controversial AI-robot stock photography that is sort of obligatory for articles like this, and just decided to post an iconic (and one of my favorite) paintings].