Discover Magazine considers the possibility surrounding one of the more challenging disorders to diagnose — late onset schizophrenia in women.

It’s well-known that schizophrenia tends to manifest for men in their late teens-early 20s, and for women, a bit later than that.

But in some cases, it begins even later — in the 40s to 60s — and women are much more vulnerable to this kind of late-onset schizophrenia.

Unfortunately, diagnosis is difficult.

The first symptoms tend to look similar to those of other mood disorders, and so women are often treated as if they have a depressive disorder.

Complicating things further, some doctors even diagnose this cohort with early-onset dementia.

Obviously, that’s bad for a number of reasons, first and foremost, being treatment.

So scientists say that a) more doctors need to be on the look out for late-onset schizophrenia and b) we need to understand why women are so much more vulnerable.

Researchers tells Discover Magazine that it might be due to declining estrogen levels.

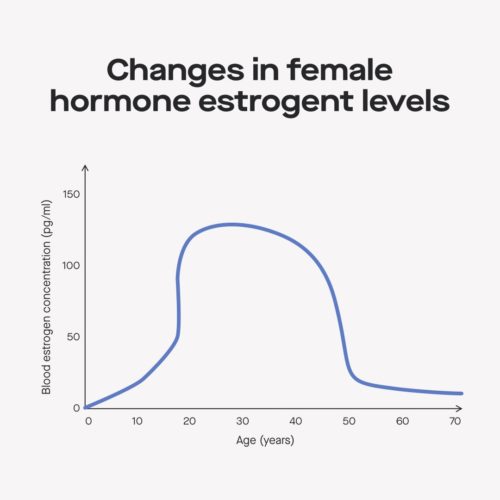

Late-onset schizophrenia occurs at age 45. Scientists think it might be timed with a woman’s decreasing estrogen as she enters perimenopause.

“The idea is that estrogen exerts protective effects so during the time when women have a lot of estrogen in their bodies, they are protected in ways from developing schizophrenia,” [Massachusetts General Hospital Associate Psychiatrist Abigail] Donovan says.

The estrogen theory would also suggest that women with lower levels of estrogen are more vulnerable to the disease, including women who have naturally lower levels of estrogen as well as postpartum women experiencing hormonal fluctuations.

The estrogen theory is still being explored, and although Donovan says many scientists support it, they want to study it more and “prove it beyond a shadow of a doubt.”

However, women with late-onset schizophrenia tend to have milder symptoms, which is good in that — well, the symptoms are milder — but it makes things more difficult because diagnosis gets much tougher.

Ultimately, researchers say doctors need more awareness so they can treat the disorder more effectively.

(And by the way, if you want to read more about estrogen levels and mood disorders, here’s a really good study from Advances in Nursing Science, concluding).

Results indicate that sudden estrogen withdrawal, fluctuating estrogen, and sustained estrogen deficit are correlated with significant mood disturbance.

For more reading, Current Psychiatry Review published a study on the neurobiological underpinnings of the estrogen-mood relationship, noting that the menopausal transition is a particularly vulnerable time for women in experiencing both new onset and recurrent depression.

That, of course, fits with Discover Magazine’s discussion of late-onset schizophrenia, and is another good reminder that if you’re going through menopausal transition, it’s good to be aware that mood disorders often come with the territory, and this is another example of why mood disorders have nothing to do with spirituality.

If you’re going through menopausal transition, and suddenly don’t feel the joy of the Lord, don’t let the “pray more” crowd distort the clear medical evidence that it is much more likely an issue of estrogen (or another medical factor) than anything else.

[Graph, via Modern Fertility]