Although written in 1966, it sounds and reads like something from many centuries past.

Which isn’t a good or bad thing, it just means you have to think longer about each line (and spending a bit longer on anything is a good thing).

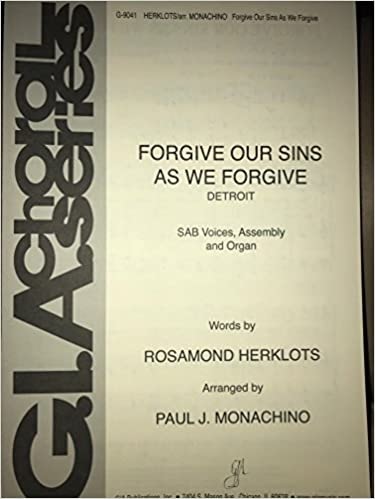

Rosamond Herklots’ song: (Why, oh, why, isn’t there more about this amazing woman and poet, online)?

*****************************************************************************************************************************

“Forgive our sins as we forgive”

‘Forgive our sins as we forgive,’

you taught us, Lord, to pray,

but you alone can grant us grace

to live the words we say.

How can your pardon reach and bless

the unforgiving heart,

that broods on wrongs and will not let

old bitterness depart?

In blazing light your cross reveals

the truth we dimly knew:

what trivial debts are owed to us,

how great our debt to you!

Lord, cleanse the depths within our souls,

and bid resentment cease;

then, bound to all in bonds of love,

our lives will spread your peace.

*****************************************************************************************************************************

Think of those lines: “What trivial debts are owed to us, how great our debt to you.”

And: “How can your pardon reach and bless the unforgiving heart that broods on wrongs and will not let old bitterness depart?”

I’m going to try (and fail) to read that last line every day.

There’s a lot of bitterness in the world, at large, right now, and perhaps in your personal life.

Mine too.

But harboring that sin is perhaps the easiest and most pernicious, because it comes from a place of being wronged and so we’re likely to hold onto it more tightly than other sins, as we mistake it for “righteousness” when really it’s the prelude to self-righteousness and the big, horrible opera, as well.

God knows I’ve indulged, and still indulge the bitter, and it’s only when I look at Christ that I realize how wrong and ridiculous it is.

He died, willingly, for a world that wronged him, and did so saying, “Father, forgive them.”

How can I make myself higher than Jesus, which is what I do when I’m bitter?

I don’t talk much about sin here because Christians with mental health challenges are particularly prone to self-loathing.

And when we fixate on sin, a lot of us talk ourselves out of Christ’s love for us. Which I’m pretty sure he doesn’t want us to do.

But it’s good to think about our sin of bitterness — not to condemn ourselves — but because it stops us from condemning others. Whether it’s condemning our spouses, our families, or our neighbors with the yard signs we don’t like.

And it’s because we’ve forgotten the theology of our fallibility, our personal sin, God’s mercy towards us, and the practice that should come from those three things — humility.

We will never let go of our self-righteousness until we see your own unrighteousness. (When we meet Jesus, I don’t think he’ll do a slow clap and say, “Wow. You were right on a lot.”).

Yet we slow clap our rightness all the time, don’t we? In our marriage, our friendships, our politics.

That’s what leads to our bitterness. Over marriage, friendship, and politics.

This is a terrible time of bitterness in America, and unfortunately, the evangelical church is feasting on it and actually promoting it. It’s like a virus that replicates and spreads, and it’s infected the entire church.

But it’s killing us, both spiritually, and as a group of people that are supposed to represent God’s love.

If there’s one fight Christians should actually be a part of in this world, it’s the fight against bitterness, the fight against our lack of humility and our self-righteousness.

(And I write this to remind myself of my own bitterness, not to put myself above it. Ask my wife about how well I deal with bitterness).

Professor Michael Hawn has written a great history of the song, and includes this beautiful anecdote.

I was in South Africa in 1998 during the presidency of Nelson Mandela. Arch Bishop Desmond Tutu presented President Mandela with the bound volumes containing the results of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I was sitting among a group of black and white Methodist ministers watching this historic occasion on television as Tutu referenced one of the many important revelations that took place during the process that the Commission hoped would lead to healing and hope for South Africa. At one point, Tutu recalled a black woman who asked him, “Who murdered my husband?” Tutu responded, “We do not know.” She was insistent, however, and continued, “I must know who killed my husband.” Again, the patient Tutu responded, “I’m sorry, but we may never know who killed your husband.” Still her question persisted. Finally, Tutu asked, “My dear lady, why must you know who killed your husband?” She responded simply and quietly, “So I can forgive him.”

I’ve included, at the bottom, Koine’s version of the song, which sounds a bit like it’s from a Sergio Leone film.