(Note: I posted this earlier this year, but occasionally repost something particularly important that fits with this site’s thesis).

Yet another compelling study shows the medical component of depression.

Researchers at McGill University looked at the cellular composition of brains from people who died by suicide vs. those who died suddenly by other means.

And what did they find? A very important difference.

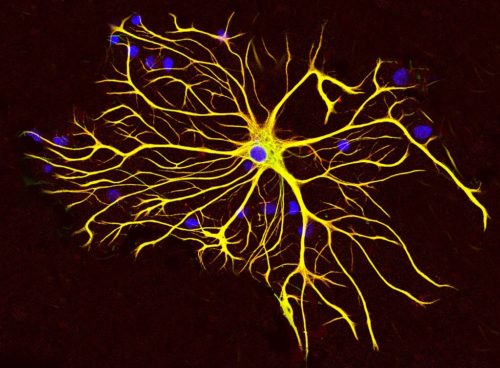

The suicidal brains had far fewer astrocytes, which are glial cells in the brain.

You can see why astrocytes, theoretically, might be important.

“They perform many functions, including biochemical support of endothelial cells that form the blood–brain barrier,[1] provision of nutrients to the nervous tissue, maintenance of extracellular ion balance, regulation of cerebral blood flow, and a role in the repair and scarring process of the brain and spinal cord following infection and traumatic injuries.”

In fact, abnormalities have been linked to numerous, other neurodegenerative diseases.

But the point is — depression, as well.

And within the group that committed suicide, there was a significant deficit of astrocytes compared to those who died suddenly by other means.

“Our study provides a strong rationale for developing drugs that counteract the apparent loss of astrocytes in depression,” says O’Leary.

“No antidepressants have yet been developed to target these cells directly, although the leading theory for the rapid antidepressant action of ketamine, a relatively new treatment option, is that it corrects for astrocyte abnormality.”

Besides the promise of potentially effective new drugs, there’s one more positive to come from this, the authors note.

“This research indicates that depression may be linked to the cellular composition of the brain. The promising news is that unlike neurons, the adult human brain continually produces many new astrocytes. Finding ways that strengthen these natural brain functions may improve symptoms in depressed individuals,” says Mechawar.

Very few think of suicide in medical terms. It’s time we started to.

I recently asked Christian philosopher J.P. Moreland about this, and here’s what he had to say:

“There are two ways one can have moral culpability.

One is if, at the time you act, this was an action that you had the free power to refrain from doing, but you freely chose to commit the action, and you knew what you were doing.

You were in possession of your faculties and you had free choice. That’s clearly something for which you’re culpable.

There’s another kind of culpability and that is when you perform an action that’s wrong, but at the point that you do it, you’re not free to say “no” to it. Because it’s the result of an addiction or the result of a character that’s been formed over a long period of time that’s lost its freedom in a certain area.

Now can you be culpable for that? Well, yes — if when you started going down the pathway that led to the point where you no longer were free to resist in this area – you had the freedom to choose not to go down that pathway.

You’re responsible – not because you’re free at the moment you act – but because you were free to not get into the position where you couldn’t help yourself.

So there can be a culpability that is transferred from past freedom to the present action.

In cases of suicide, there are times when the person could have, earlier on, started making choices to get counseling and help so that they didn’t get to the point where they were so blown out in their brain chemistry that they couldn’t help themselves.

But I think a lot of suicides are the result, like dementia, of an action that is not the result of something you failed to do freely, early on.

Sometimes things happen to people, through no fault of their own, and it overwhelms them, and they’re triggered in a way that is not controllable.

I think sometimes PTSD occurs with such severity that it actually constrains their freedom, and their behavior is not something they’re freely responsible for.

Just like a person with dementia who starts treating people badly – it’s not an action they’re performing. It’s something that’s messed up with their brain.

I think, in those cases, there’s probably not culpability because there’s not an ability, through no fault of their own, to consider what they’re doing and realize it’s selfish.

It’s sad, but in those particular cases, I would say there’s not a moral culpability because they weren’t able to choose to do otherwise – for reasons not of their own choosing.”

[Photo: Gerry Shaw, Wikipedia]